The Moderating Role of Gender in the Relationship between Youths' Internalizing Symptoms and School Climate

- Nov 14, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Nov 18, 2025

In November 2025, Kelly Lojinger led a poster presentation at the annual convention of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies summarizing the results of her thesis, using data from the ESSS study. A summary of that presentation is below, along with the handout.

Introduction

Internalizing disorders, such as anxiety and depression are among the most common mental health concerns for children and adolescents (Racine et al., 2021). Research suggests that school environments can influence internalizing symptoms in youth (de Arellano et al., 2023). Positive school climate has been shown to be a protective factor for mental health outcomes and contributes to resilience for many at-risk youth (de Arellano et al., 2023; Shochet et al., 2006). Gender has been found to impact the relationship between internalizing disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression) and school climate (Bhat & Mur, 2018; Lester et al., 2013; Way et al., 2007).

Current Study

Sixteen elementary schools in the southeastern U.S. participated in a four-year study examining strategies to improve social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes for students (details here). Students completed measures of school climate and internalizing symptoms over the course of three years (Fall 2022 – Spring 2025). Methods

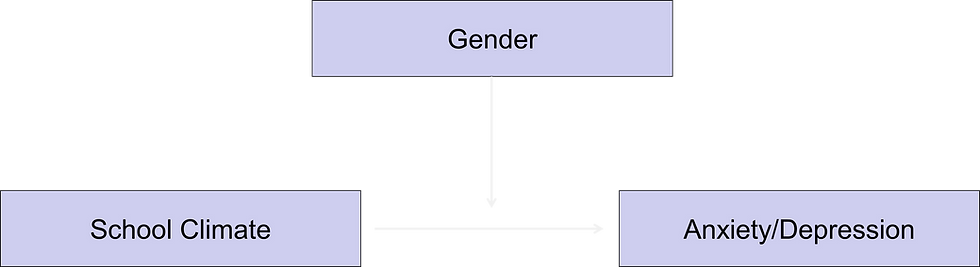

We collected baseline data, prior to intervention, for 1,030 third grade students (Girls: n = 507, Boys: n = 523). Participants rated their own symptoms of anxiety and depression (PROMIS® Measures; DeWalt et al., 2015), as well as overall perceptions of school climate (Center on PBIS, 2022). We then examined whether the strength of the relationship between school climate and internalizing disorders varied by gender (moderation model below).

Results

Moderation Model Predicting Anxiety

| Predictor | b | SE | p |

Block 1 | (Intercept) | 25.19 | 1.64 | <.001 |

PBIS School Climate | -1.64 | 0.43 | <.001 | |

| Gender (Boys = 1) | -2.96 | 0.46 | <.001 |

Block 2 | (Intercept) | 27.96 | 2.18 | <.001 |

| PBIS School Climate | -2.51 | 0.63 | <.001 |

| Gender (Boys = 1) | -7.89 | 2.63 | .003 |

| PBIS School Climate: Gender | 1.60 | 0.84 | .056 |

Moderation Model Predicting Depression

| Predictor | b | SE | p |

Block 1 | (Intercept) | 30.07 | 1.72 | <.001 |

| PBIS School Climate | -3.84 | 0.46 | <.001 |

| Gender (Boys = 1) | -2.30 | 0.48 | <.001 |

Block 2 | (Intercept) | 32.62 | 2.31 | <.001 |

| PBIS School Climate | -4.65 | 0.67 | <.001 |

| Gender (Boys = 1) | -6.83 | 2.77 | .014 |

| PBIS School Climate: Gender | 1.47 | 0.89 | .098 |

Block 1 of each regression analysis examined the relationship between perceptions of school climate and internalizing symptoms (i.e., anxiety and depression) while controlling for gender. Significant main effects suggest that as perceptions of school climate increase, internalizing symptoms decrease when controlling for gender. Boys reported less anxiety and depression overall than girls when controlling for perceptions of school climate. Block 2 of each regression analysis examined the degree to which perceptions of school climate on internalizing symptoms is dependent on gender. Gender did not significantly moderate the relationship between perceptions of school climate and symptoms of anxiety and depression. The relationship between school climate and internalizing symptoms did not appear to depend on gender; in other words, the influence of school climate on anxiety and depression was not significantly different for boys and girls.

DISCUSSION

Our findings offer support for the importance of promoting a positive school climate to buffer internalizing symptoms for both boys and girls in elementary schools. To promote positive outcomes for students, educators might build an environment where youth feel as part of a school community and can receive individual support as needed (see Renick, Reich, & Phan, 2025). Our results suggest that school climate does not affect internalizing symptoms for boys and girls differentially; but this finding does not suggest that efforts to alter climate-focused interventions for individuals based on gender-related concerns are unhelpful or unnecessary.

Limitations: Participants in this study included a sample of elementary-age students in two U.S. states with data analyzed from one measurement occasion, so our results may not speak to other geographic regions or to youth perceptions over time. Our results also do not speak to gender diverse youth, who might benefit from individualized supports to improve climate-related concerns, like school connectedness (Ioverno & Russell, 2022).

Conclusion: We interpret our results to suggest that a positive elementary school climate can help prevent symptoms of anxiety and depression for both boys and girls. Separate gender-specific efforts to improve school climate at the elementary level may be unnecessary.

Handout below:

References

Bhat, M. S., & Mir, S. A. (2018). Perceived school climate and academic achievement of secondary school students in relation to their gender and type of school. Online Submission, 3(2), 620-628.

Center on PBIS. (January 2022). School Climate Survey (SCS) Suite Manual. University of Oregon. www.pbis.org

de Arellano, A., Neger, E. N., Rother, Y., Bodalski, E., Shi, D., & Flory, K. (2023). Students' ratings of school climate as a moderator between self-esteem and internalizing symptoms in a community-based high school population. Psychology in the Schools, 60, 4701–4720. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22999

DeWalt, D., Gross, H., Gipson, D., Selewski, D., DeWitt, E., Dampier, C., et al. (2015). PROMIS® Pediatric Self-Report Scales Distinguish Subgroups of Children within and across Six Common Pediatric Chronic Health Conditions. Quality of Life Research, 1-14.

Ioverno, S., & Russell, S. T. (2022). School climate perceptions at the intersection of sex, grade, sexual, and gender identity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 32(1), 325-336. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12607

Lester, L., Waters, S., & Cross, D. (2013). The relationship between school connectedness and mental health during the transition to secondary school: A path analysis. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 23(2), 157–171.

Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

Renick, J., Reich, S. M., & Phan, H. K. (2025). Towards Developmentally Informed School Climate Research. Contemporary School Psychology, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-025-00565-4

Shochet, I. M., Dadds, M. R., Ham, D., & Montague, R. (2006). School Connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: Results of a community prediction study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(2), 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_1

Way, N., Reddy, R., & Rhodes, J. (2007). Students’ perceptions of school climate during the middle school years: Associations with trajectories of psychological and behavioral adjustment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40(3–4), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9143-y

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research reported here was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant R324A210179 to East Carolina University and the University of South Carolina. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.

on gender.

Comments